A Tale of Two Worlds in Today’s China

Back in the late 60’s, when I was 12 years old, my parents went through re-education during the Cultural Revolution.

Our family moved from our home in Shenyang, an industrial city in the northeastern China, to DaQing Commune 40 miles north of the city. We lived there for three years, during which I had a delightful time. It nurtured my childhood whimsies and cultivated memories I still cherish today. I visited DaQing last October for the first time since our family moved back to the city half a century ago, the trip bringing back many fond memories and, at the same time, evoking weighty mixed emotions.

The Old Days

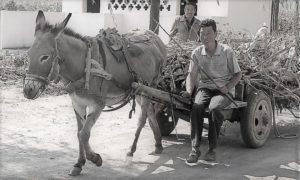

In those days, DaQing had one dusty main street about 100 yards from our house, the only thoroughfare cutting through the village bustled with a vibrant scene. All day long Horse-drawn wagons kicked up clouds of golden dust while much smaller donkey-pulled carts clopping on alongside. The air was filled with the sounds of horse drivers shouting and, hoof beats, as hurried villagers headed to the marketplace with produce in tow. Ducks, unfazed by the steady commotion, were waddling in single-file, dodging traffic on the way to a nearby pond. And flocks of chickens were busy picking the earth.

I was often hypnotized by the lively scenes for an hour or two, particularly fascinated by the big boys waving long whips in the air to control three or four jumpy horses pulling heavily loaded wagons. Now, having lived in America for more than 30 years, I am often drawn into old western movies, the sentiment that appeals to me, transporting me right back to that part of my good old childhood days.

Another side of China today

After fifty years, I met up with my close childhood friend in DaQing, WanJiang. He married a city girl later on and relocated to Shenyang, the same city where I grew up. He gladly agreed to go back with me to DaQing Village. Commune, once a common name for countryside organizations all over China, is no longer in use now since the economic reform 30 years ago. It took us 1.5 hours to get there by air-conditioned tour bus on the newly paved highway. However, this same trip, in the old days, would have taken more than half a day. We would take the train and bus, then one more hour by horse-drawn wagon–the latter actually being my favorite part of the journey to this day.

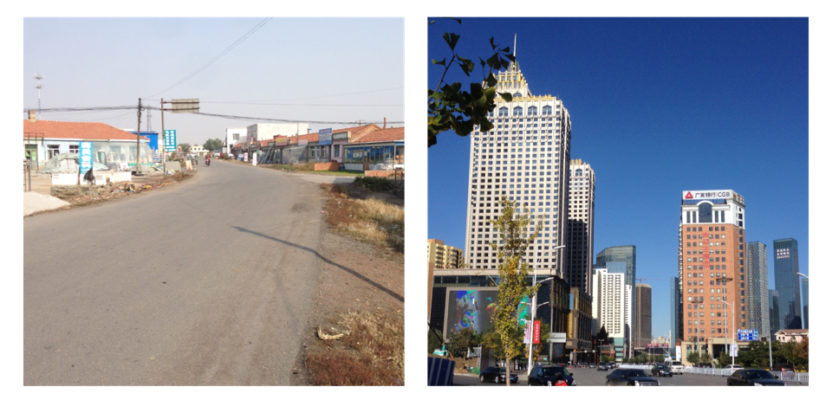

If WanJiang did not tell me where we should get off from the bus, I would never have recognized it. Standing in the middle of the road about 100 yards from where my family’s house used to be, I gazed around and my heart sank instantly with a strong sense of melancholy. On and along this same thoroughfare today, I was missing the horses, wagons, donkeys, and even the running chickens and ducks. But most of all, where were all the villagers? Instead, as far as my eyes could reach were outgrown weeds by the roadside and on the rooftops of what used to be the largest General Store building. It was still dusty but eerily quiet in the middle of a sunny day.

If WanJiang did not tell me where we should get off from the bus, I would never have recognized it. Standing in the middle of the road about 100 yards from where my family’s house used to be, I gazed around and my heart sank instantly with a strong sense of melancholy. On and along this same thoroughfare today, I was missing the horses, wagons, donkeys, and even the running chickens and ducks. But most of all, where were all the villagers? Instead, as far as my eyes could reach were outgrown weeds by the roadside and on the rooftops of what used to be the largest General Store building. It was still dusty but eerily quiet in the middle of a sunny day.

Not as what I had expected

Enthused and desirous nonetheless, we walked around the village and through a few alleys full of loose bricks and muddy potholes. Along the way, WanJiang pointed to those places where our houses used to be, where we used to go to a pond to skate in the winter and bathe in the summer after school. My favorite memory stirs from the site where a large cow-shed used to be, from where we each would be riding a cow to herd a dozen of other cows to the remote fields for grazing.

Today I saw nothing that resembled these memories. Instead, I was in a daze facing the emptiness and lifelessness filling these spaces and, thus, gripping on my heart. As much as I understand that much has changed over the years, but I did not expect to find what could only be described as a post-apocalyptic scene just a short drive away from a thriving city of eight million people! And I, for one, go back to my home city every year and countless other places around China. Apparently, there is another side of today’s China that most people don’t get to see, myself included.

How are those childhood friends?

Dismayed and saddened by what I saw, a picture completely not what I had in mind, I gave up reminiscing about the old times. I then asked WanJiang to look for the local childhood friends, whose families had been here for generations. The good news is that everyone knows everyone in this 400-household village, except our family since we were outsiders back then. We started to knock on a few doors and WanJiang mentioned some names to the very old people staying at home. We found two other elementary classmates in no time.

One girl, in my memory, was a model student by any measure in those years. She was quiet but often raised her hands to answer questions in class. Shy as she was but always ready to assist others with their homework problems. She dressed simply but fit and spotless. She never left that village, currently running a tiny food store without a storefront sign. It took us a while to find her store even though we knew the name. The wind blew away the sign and she simply had never replaced it. She told us.

“Everyone knows me and this store, why bother to have a sign?” She said unfeelingly when I brought it up as my ice-breaking line while we were staring at each other, attempting to pinpoint some trace of old-time recollections.

Another gentleman, who was also from the same class five decades ago. He was overjoyed to see me when he learned that I came from America, halfway around the world, just to see DaQing again. Somehow, I could not recall his name and felt too uncomfortable to ask the entire time.

Food is even better today

Four of us walked into the only restaurant in the village, where only one other table had a few people sitting around. They were, like me, just passing through. A lady, who was both the owner and chef, greeted us. Her plump face was bursting into a smile like a summer sunflower. I then noticed that their “menu” was simply a display in their kitchen, similar to a produce stand in the marketplace. The “menu” was rich in exhibits, nevertheless, with all kinds of fresh vegetables, pieces of fresh pork and chicken. My eyes lit up when I spotted a huge water tank with live fish circling in it. Each fish weighed about 5 lbs. and they caught the fish right from the lake a stone’s throw away from the back door.

“What do you have for meals?” I asked.

“Anything here you can see,” the owner-chef lady, still smiling, answered readily, her chin pointing to her menu on display.

“How do you cook the fish?” My eyes locked in on that fish tank.

“The best way I know.” Obviously, she never feels the need to name any of the dishes, let alone to describe how she cooks all the food; thus, a conventional menu serves no purpose in her restaurant.

There is no more authentic Chinese family cooking than this–no recipes and no measurements. The ingredients used to cook the dishes will change from time to time or even from dish to dish—you only cook what you grow for the season. Farm-to-table is not a new trend here. It was, and still is, the only way people prepare food in this village. I suddenly felt more at home now sensing the indigenous sincerity in her tone. It took me back to the old days 50 years ago.

Why are things like that?

We sat at a table sipping tea, catching up on the half a century that had slipped away, while waiting for our food.

“Where are all the people here?” My very first question on my mind, since the moment I stepped off the bust, burst out irrepressibly.

“All the young and abled people have left to look for work in the cities.” The answer came out just as irrepressible from the second gentleman. “I’m too sick to leave.” He said, ending it with a sigh.

“I need to take care of my mom every day as she has not gotten up from bed for about a year already. And she never will.” The model student mumbled, while her eyes staring down at her tea. It was nothing like in the old days when she answered teacher’s questions in class.

“Why are the road conditions still so bad?” I couldn’t hold my second question any longer.

“We can’t afford a new road, even when the government promises to pay half of all the costs.” The model student simply stated. “Anyway, this place is my home, and it has all the things I need.” She continued, sensing more questions in my eyes, “Life is easy here.”

While catching up, we finished eating, with half the fish still untouched among other leftovers. The chef-owner lady simply cooked too much. The meal cost $15.00 for the four of us, including beer and their homemade rice wine. I came to understand a little more about what she meant by “life is easy here”.

A night view of Shenyang, my hometown today

Back to the familiar China

On the bus ride back to my home city Shenyang, skyscrapers illuminated half the sky from the distance. My journey was like examining a prehistoric world only to return to a contemporary one. Suddenly, I realized those who built the state-of-the-art parts of China, the miracles that the whole world recognizes nowadays. Officially, they are migrant workers with no social status in the cities. They abandoned their own homes where their families had made roots for generations. And they came out to the cities to build better homes and better lives for others.

If the present-day marvels in China are made by the hands of hundreds of millions of migrant workers–and they are, like those at iPhone assembly lines and construction sites all over the country—then, at least, the world should know that they are still doing it today. And they often must go through hardships far beyond what most people could have imagined.